On May 25, Reuters reported that Canadian privacy regulators are launching a joint investigation into whether OpenAI has obtained consent for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information of residents via ChatGPT.

While that is certainly a question worth investigating, there are other questions concerning AI that also warrant investigation in terms of research and consent for data collection and use. This week, PogoWasRight.org submitted a complaint and inquiry to Canada’s Commissioner of Privacy and the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta stemming from a data leak involving mental health-related information that appeared to be collected by university researchers.

Background on the Data Leak

In early April, I was contacted by someone who had stumbled across unsecured data. He was concerned because it appeared to contain sensitive personal information on the mental health of identifiable individuals.

The database, called “Crate DB,” had nothing that identified who owned the database or whom to contact about it. Inspection revealed file names that pointed to the University of Calgary, the University of Alberta, and to a lesser extent, McGill University. The data appeared to be from social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram and to have been scraped from those platforms.

Some of the topics appeared to be fairly innocuous or environmentally related, but the big concern was that the researchers seemed to be collecting tweets and material from identifiable individuals or accounts related to mental health.

At the time I viewed the unsecured data, one table called diagnosed_tweets had 2.4 million records (5.1.GB) and another table called diagnosed_users_metadata had 15,368 records (10.4 MB).

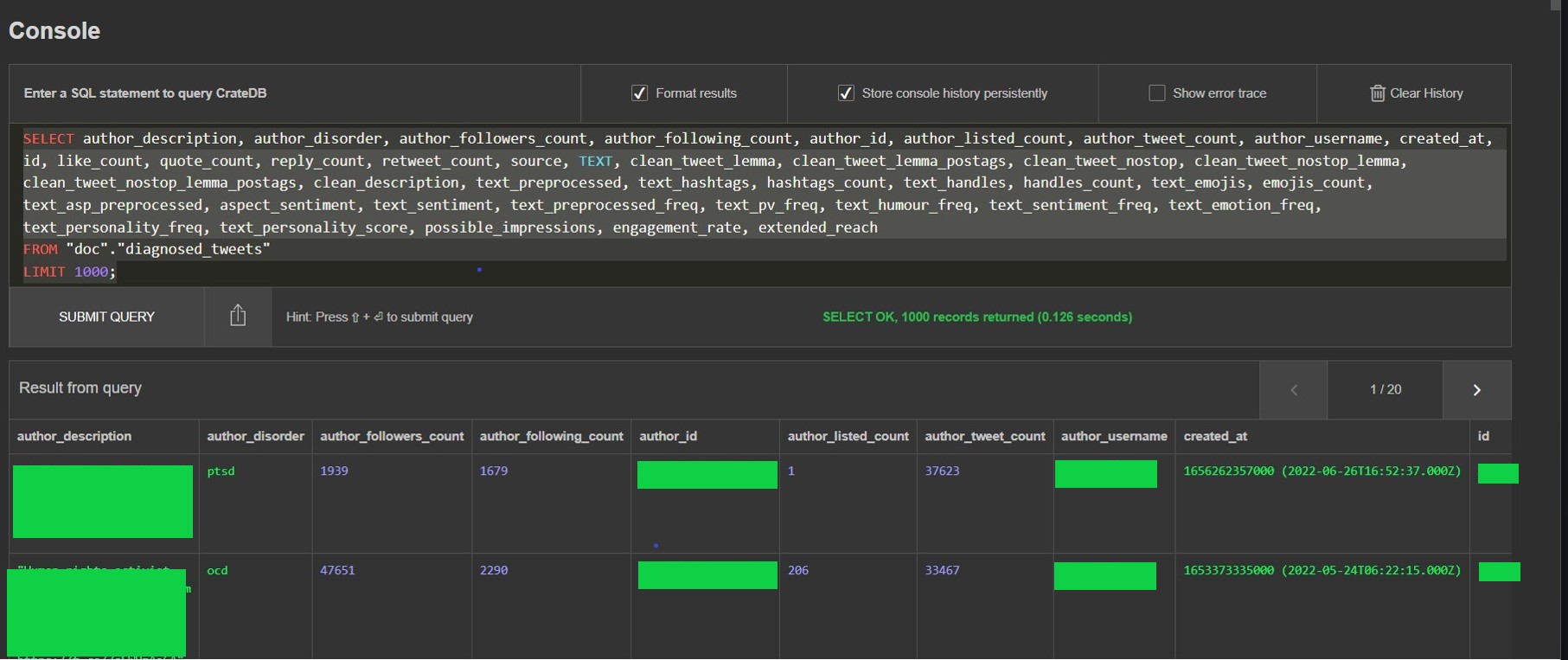

The diagnosed_tweets table had the following fields:

author_description, author_disorder, author_followers_count, author_following_count, author_id, author_listed_count, author_tweet_count, author_username, created_at, id, like_count, quote_count, reply_count, retweet_count, source, TEXt, clean_tweet_lemma, clean_tweet_lemma_postags, clean_tweet_nostop, clean_tweet_nostop_lemma, clean_tweet_nostop_lemma_postags, clean_description, text_preprocessed, text_hashtags, hashtags_count, text_handles, handles_count, text_emojis, emojis_count, text_asp_preprocessed, aspect_sentiment, text_sentiment, text_preprocessed_freq, text_pv_freq, text_humour_freq, text_sentiment_freq, text_emotion_freq, text_personality_freq, text_personality_score, possible_impressions, engagement_rate, extended_reach

In the above figure, which I have redacted, the first column is called author_description. That field is the individual’s self-generated profile on Twitter. From the description, it would be easy to find the individual’s Twitter account by copying the description and pasting it into a Google search. But it’s not even necessary to do that because the author_id field (also redacted) and author_username fields would also allow you to immediately identify the individual.

The second column in the figure is “author_disorder.” For the first individual, it says “ptsd.” For the second individual, it says, “ocd.”

If you were to be able to view the complete table in a single screencap, you would see that for the first individual (the one with “ptsd”), the researchers also recorded the number of “likes” to the tweet, the number of re-tweets, the number of quotes, and the number of replies. The source of the tweet (“Twitter for Android”) was also recorded, as was the entire text of the tweet itself, including the usernames of those to whom it had been addressed.

In the figure below, you can see a few entries from the diagnosed_users_metadata table that have been. The fields for that table are: profile_image_url, created_at, username, verified, url, protected, description, NAME, followers_count, following_count, tweet_count, listed_count, author_id, author_disorder

Once again, there was identifiable information on users that would allow anyone to find their accounts on social media. Their usernames, account IDs, profile descriptions, and other details are all now publicly linked to mental health diagnoses.

Did any of these individuals consent to have their tweets and any mental health issues compiled in a publicly available storage container like this? Did any of them consent to having any of their data used for any mental health study at all? Are any of them minors who might subsequently regret their tweets and want to delete all of their activity? And are these self-diagnoses or diagnoses by mental health professionals?

Responsible Disclosure, but Not a Responsible Response?

On April 11, I contacted the University of Alberta and the University of Calgary by separate emails to alert them to the exposed and unsecured data and to ask them about the unsecured mental health-related information. Someone from University of Calgary’s cybersecurity department called me later that day. I gave them the URL of the exposed container, and within 24 hours, the data were no longer publicly available. But no one ever responded to my questions about who had been responsible for the database’s security, who was responsible for the collection of the mental health-related data, and whether they had obtained consent or institutional review board approval.

On April 30, I wrote both universities again. The University of Alberta never replied to either email, even though an IP address lookup had indicated that the IP address of the exposed data was owned by them. Someone from the University of Calgary did respond to my second email and told me they would look into it, and “if there was a research ethics breach we will investigate.” But she, too, never got back to me to inform me whether there had been an ethics breach or what they had found.

And so I filed a formal complaint with the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta (both the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta are in Alberta). I posed the following questions to the commissioners:

- Can a public research university collect data containing personal and sensitive information from and about identifiable individuals on social media without their knowledge or consent?

- Does Canadian privacy law or Alberta provincial law take the position that whatever people post on publicly available platforms is therefore freely available to researchers and does not require consent to use for AI or other research? If so, should that be changed?

- What data protection or data security requirements apply to the type of tweets and user information collected and stored online by the researchers in this situation? Were data security laws violated by having an unsecured container like this with mental health-related content?

- Since neither university admitted any responsibility and the IP address points to the University of Alberta:

- Which university was responsible for CrateDB?

- Who were the researchers who were responsible for CrateDB?

- Which university was responsible for the mental health data questions and the associated data collection?

- Did the researchers involved in the mental health data seek and obtain any institutional approval for collecting and storing the data that was collected?

- Does anyone at the responsible university know whether any of the individuals whose data they collected, processed, and stored are minors?

- If the research violated any information and privacy laws, will the researchers be directed to delete all the mental health-related data?

I do not anticipate getting any kind of quick response, but I do hope the commissioners look into this incident and also think about the issues more broadly in terms of scraping publicly shared information related to personal and sensitive topics. Even if the data are then de-identified, who stored the original data and who has access to it, and did anyone ever consent to their data being collected or used this way?