Seen recently on my favorite newsletter, Risky Biz News:

Google changes privacy policy: Google has changed its privacy policy to let its users know that any publicly-available information may be scanned and used to train its AI models. It’s funny that Google’s legal team thinks its privacy policy is stronger than copyright law. Hilarious!

That gave me pause, because I’m not sure about this at all. Could using publicly available info to train AI be considered “fair use?”

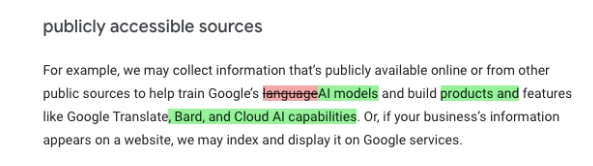

For those who haven’t seen it, Cointelegraph reported the change in Google’s policy by highlighting the additions (green) and a deletion (red) from the previous privacy policy on publicly accessible sources:

Is collecting publicly available posts and material — including publication of copyrighted material — really a copyright violation if the material is not being republished but is just being used for other purposes? Is it really a privacy violation to collect and use material to train AI?

PogoWasRight (PWR) reached out to the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) to ask them for their position on Google’s policy changes and whether they violate privacy law or copyright law. Rory Mir kindly shared his thoughts about the questions I posed to them.

PWR: Is Google violating privacy by collecting publicly posted material or does the ‘no expectation of privacy in public” apply here?

RM: The AI data discussion is struggling with intended use of publicly shared information— namely, that it is usually intended for a human to read and not feed some algorithm. However, it is important for Fair Use to defend uses beyond what is intended, even when copyrighted. That’s how people can do things like review a film; remix a song; or archive the tweets of a notable figure.

That said, there is an onus on AI developers to be responsible stewards of their training corpus. The default seems to be web scraping *everything*, have minimally paid and outsourced labor prepare it for training, and playing whack-a-mole when filtering the output.

It’s important for these companies to take steps to do better. Being clear about what information is used in training, and ideally adopting a more Open Data and Open Source approach, is vital. It may not be possible to ensure the resulting model doesn’t spit out this initial information, so it shouldn’t be trained on something they wouldn’t otherwise share publicly.

Another promising solution would be to empower users and hosts to opt-in to this sort of training. Google seems to be considering a model similar to robots.txt, which currently tells its web-crawlers what to collect on a given site. Whatever comes out of this, the solution ought to empower users as well as hosts, as is often the case in search.

Ultimately we need well maintained and transparent datasets built by consenting participants— any shortcuts in this regard only increase the likelihood of AI having a harmful impact.

PWR: Does TOS (terms of service) cover Google now they have published that revised policy?

Unfortunately TOS agreements are outside of my expertise, but much of this would already be covered by Fair Use. TOS may be relevant if they start using private user data in training, though, which should always be opt-in if offered at all.

PWR: If they are using the material to train AI, does that mean that they are storing deanonymized data that may be something individuals would like forgotten or deleted?

It’s difficult to say “storing” in this context, but it’s possible for an AI model to reproduce content it was trained on, at least in part. This is less likely for more general prompts, but a narrow prompt in an area where there are few or very unique examples may reproduce identifiable information. There are even some reports of chatgpt producing valid windows registration keys

(https://www.dexerto.com/tech/chatgpt-can-generate-windows-keys-but-its-a-bad-idea-2182178/). A unique and identifiable piece of personal information could also surface with the right prompt—since AI is an unreadable black box it’s hard to know exactly what it is capable of producing.However, it is much more common for an AI to ‘hallucinate’, with a mix of credible and fabricated information. So while not a privacy risk per se, AI (LLMs) may create things which *appear to be* a privacy violation of a real person. We’re probably bound to find examples of AI hallucinating an *accurate* privacy violation accidentally.

Either way, being able to cross-reference the underlying dataset would be essential.

PWR: Is Google violating copyright law if they index it and display it without direct consent? Is *displaying* it a copyright violation if there is no consent or is TOS implied consent here now that they’ve published that?

Much of this would be covered by Fair Use, as is the case for search engines (related case [https://www.eff.org/cases/perfect-10-v-google]). A more in-depth and legal take on generative AI and fair use is available here:[https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/how-we-think-about-copyright-and-ai-art-0].

That said, as we see in online search, major companies may also come to voluntary agreements about what to include/exclude from AI datasets— but smaller creators, and everyday users should always have meaningful ways to do the same.

So far, then, it seems like copyright law is no protection against using publicly available material to train AI models because of the doctrine of fair use.

Great thanks to Rory for sharing his thoughts and to EFF for all they do to protect our privacy and civil liberties.

And just as I was working on formatting this post, what crossed my desk but an article called, What does AI need? A comprehensive federal data privacy and security law. We may need it, but are we ever going to get one when we still don’t have any federal privacy law despite years of saying we need one?